Survivors from the days of vinyl, some Christmas albums have withstood the test of time, and the holiday season does not start for me until I choose to play my cassette of these lps that I grew up with.

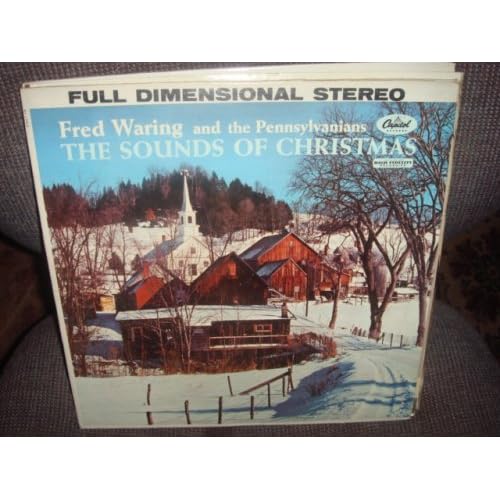

Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians The Sounds of Christmas is not available in its original configuration, but selections of it are included on this assortment of Waring releases from the 50's and 60's. (Tracks 1, 4 and 8). The original lp featured a gorgeous picture of a snowed-in Vermont village (East Corinth)? and the tunes had a continuous flow with snippets of

common carols segueing between less-well-known tunes, such as Jesu Parvule, Go Where I Send Thee, Ring Those Christmas Bells, While By My Sheep and a host of others you have never heard, but will wish you had. Beautiful part-singing and peppy late-50's arrangements are both contemporary and nostalgic at the same time. It warms the cockles of my heart to read comments on Amazon to the effect that this is one of the best– if not THE best– Christmas record ever made.

Original vinyl editions of this recording START at $200 on Amazon.

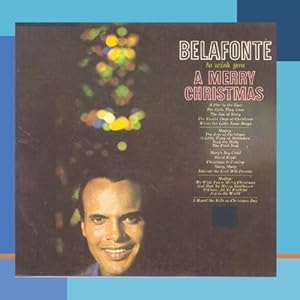

Harry Belafonte’s To Wish You a Merry Christmas IS available digitally, and it’s a blessing. This ultra smooth, understated collection of Christmas favorites and rarities has less to do with Belafonte's calypso style and more to do with music to calm you down after being pepper-sprayed at Best Buy. One of the rarities is present on both the Waring and the Belafonte collections, Rise up Shepherd and Foller; both versions are unforgettable. Word has it that when I was not able to speak complete sentences or read yet, I kept asking to hear this record, but just kept saying “Gave to me! Gave to me!” No one understood what I was trying to say, but one day when The Twelve Days of Christmas came on the radio, I nodded my head, smiled and said “Gave to me!” and the mystery was solved. “(On the third day of Christmas my true love gave to me...)”

While still a high school senior, I was a member of the Hartford Community Orchestra. They tackled challenging repertoire in my two years with them, not the least of which was Vaughan Williams’ Christmas cantata Hodie. A 16-movement work scored for chorus, boys' choir, organ and orchestra, and featuring tenor, baritone, and soprano soloists, it is full of rich, gothic, chocolaty goodness. A truly spine-tingling moment is the segue from the March of the Three Kings, in D minor, into the hymn No Sad Thought, His Soul Affright, in D♭ major. I came to love this early London recording with Dame Janet Baker headlining.

This same community orchestra the following year played Berlioz’ oratorio L'Enfance du Christ. A more involved work than the Vaughan Williams, the centerpiece of it is L'adieu des bergers (The Shepherd’s Farewell). Both this and the Vaughan Williams No Sad Thought have been performed by the KSO on Clayton Holiday Concerts, although it was likely before some of you were born.

I have some strange Christmas traditions. One of them is to listen to Emerson Lake and Palmer’s Trilogy lp every Christmas Eve. Sure, it’s not Christmas music per se, but when this was first released in 1973, it seemed like a religious experience, and I never wanted to let go of that myth. Songs like From the Beginning, The Endless Enigma and Abaddon’s Bolero were a nice backdrop to my holiday preparations, and FTB was one of the first songs I learned to play on guitar.

There is very little to say about the Rachmaninov Vespers (also known as (All-night Vigil) that doesn’t say itself, once you start listening to it. Some have gone so far to say that this is Rachmaninov's crowning achievement. Although it also is not specifically Christmas music, what could go wrong with more than an hour of a capella Russian choir singing, with sometimes up to nine voices and bass parts that will make you involuntarily look skyward and close your eyes?